The Story of Vālmīkī Rāmāyana

- Post Date: 07/15/2024

- Author: Divya Nair, Mellon Post-Doctoral Fellow in Humanities as Social Practice, Humanities Research Institute at Illinois

- Reading Time: 9 minute read

The Hindu epic Rāmāyana conveys the life of Sri Rāmā, an important deity in the Hindu pantheon, and his efforts retrieve his wife Sītā from the grasp of the demonic King Rāvanā and restore his kingdom. Though it is impossible to date it exactly, the story is said to have taken place more than 5,000 years ago, and it has been narrated orally for many millennia.

In the poet Vālmīkī’s Rāmāyana, Sri Rāmā is figured as maryāda puroshōttam, the ideal man who embodies the principle of dharma(external link). Dharma refers to a set of universal duties, such as self-control, forbearance, compassion, purity, and truthfulness, prescribed for all, as well as a bundle of prescribed duties depending one’s stage and station in life. Though his divinity is recognized by many characters in the story, Rāmā retains a profound sense of his humanity, simply for the benefit of imparting dharma in human relations.

Over the course of the epic, Rāmā maintains a firm and, some would say, uncompromising, allegiance to duty—to his mother, his father, his brothers, his wife, and, most importantly as a ruler, his subjects. Performance of duty in the right spirit is essential to virtuous governance, and Rāmā exemplified this for the people of his age and clime.

Many interpretations of the Rāmāyana understand Rāmā to be an avatar, specifically the seventh avatar of Vishnu, the deity presiding over the principle of preservation in the cosmic cycle of creation, preservation, and destruction. The word avatāra in Hinduism signifies a divine being who has taken human birth for the benefit of humanity in a given age. As Sri Krishna, the eighth avatār of Vishnu, remarks in the Bhagavad Gita, “Whenever virtue subsides and immorality prevails, then I come again and again to help the world” (Bhagavad Gita 4.7-8). The Rāmā avatar is said to have taken birth in the Treta Yuga, the second phase in the four cycles of time in the Hindu cosmology, which include Satya, Treta, Dvāparā, and Kali. The Satya yuga refers to the age when humanity lived in perfect alignment with truth as gods. According to the yuga theory, in each subsequent phase to the Satya yuga, human beings become alienated from their divinity.

-

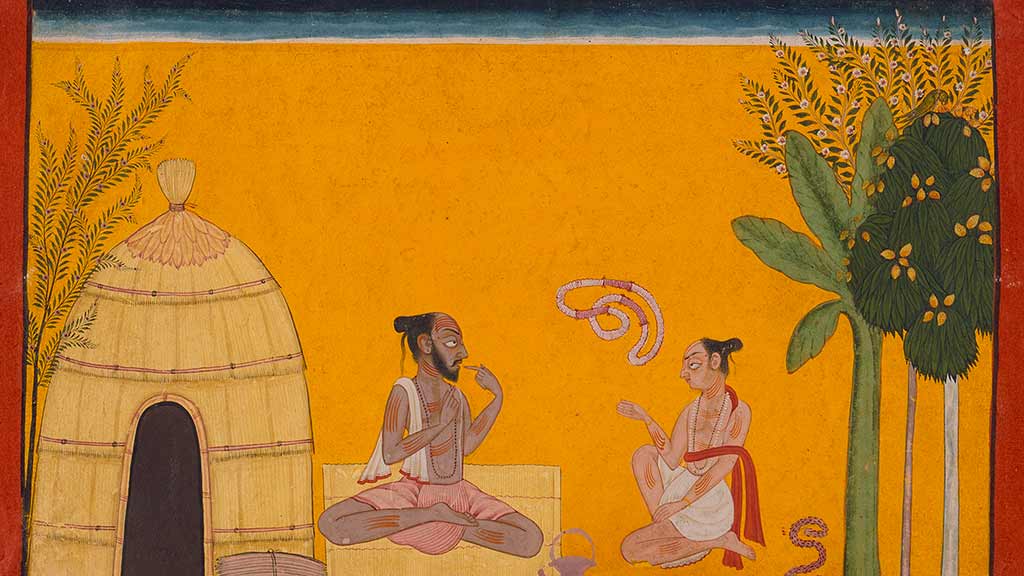

The Sage Valmiki Describing the Origin of the Verse Form He Later Used to Compose the Rāmayanā to His Pupil Bharadvaja, Folio from the “Shangri” Rāmāyana (Adventures of Rāmā) India, Jammu and Kashmir, Bahu, circa 1700-1710. LACMA(external link)

The Sage Valmiki Describing the Origin of the Verse Form He Later Used to Compose the Rāmayanā to His Pupil Bharadvaja, Folio from the “Shangri” Rāmāyana (Adventures of Rāmā) India, Jammu and Kashmir, Bahu, circa 1700-1710. LACMA(external link)

Vālmīkī is an ancient poet-sage to whom the Rāmāyana is often attributed, though it is worth noting that there are myriad versions of the Rāmāyana on the Indian subcontinent in various languages. These interpretations do not necessarily adhere to the same turns of plot though the main characters and central dilemma remains consistent. The most ancient language in which it was rendered, however, was Sanskrit, the language of the Indo-Aryans. In his 1900 lecture(external link) to the Shakespeare Club in Pasadena on the Rāmāyana, the Hindu monk Swami Vivekananda observed that “a great many poetical stories were fastened upon that ancient poet; and subsequently, it became a very general practice to attribute to his authorship very many verses that were not his.” As the French poet Leconte de Lisle put it in his poem “La mort de Valmiki,”

Valmiki, le poéte immortel, est trés vieux. Toute chose èphèmére a passè dans ses yeux, Plus prompte que le bond lèger de l'antilope.Valmiki, the immortal poet is very ancient, All things ephemeral passed before his eyes, More quickly than the light leap of an antelope. Leconte de Lisle

The Rāmāyana is divided into seven kāndas or sections: Bala Kānda, Ayodhya Kānda, Aranya Kānda, Kishkindhā Kānda, Sundara Kānda, Yuddha Kānda, and Uttara Kānda. Each kānda depicts a major episode in the life of Rāmā. Bāla Kānda narrates the story of Rāmā’s auspicious birth and his childhood and his marriage to Sītā. Ayodhya Kānda depicts their life in Ayodhya. Here, the maid Manthara poisons Rāmā’s stepmother Kaikeyi’s mind on the eve of his coronation, when she convinces Kaikeyi that her son Bharatā should be ruling instead. Rāmā’s father Dasaratha banishes him to the forest, where he is joined by his wife Sītā and his younger brother Lakshmanā.

Aranya Kānda focuses on the journey of the three exiles into the forest, where they encounter various personages, including demons (rākshasas) who are attacking the hermitages of sages (rishis). Sītā is abducted by Rāvana, king of these rākshasās. Kishkindā Kānda is about Rāmā and Lakshamā’s search for Sītā, which leads them to the Vānara kingdom, where they enlist the aid of the chieftain, Sugrīva. Sugrīva is himself besieged by his brother’s usurpation of his throne. Rāmā and Lakshamā’s powerful ally Hanumān bravely ventures in search of Sītā with the Vānara army.

Sundara Kānda focuses on Hanumān’s discovery of Sītā’s location in Rāvana’s kingdom in Lanka. Yuddha Kānda relays the great battle between Rāmā and Rāvana, culminating in the death of Rāvana and the victory of Rāmā. Rāmā returns with Sītā and Lakshmana to rule Ayodhyā, the subject of the Uttara Kānda.

-

- Share: 𝕏

- Subscribe to Newletter

- Giving