Global Receptions of the Rāmāyana

- Post Date: 07/22/2024

- Author: Divya Nair, Mellon Post-Doctoral Fellow in Humanities as Social Practice, Humanities Research Institute at Illinois

- Reading Time: 15 minute read

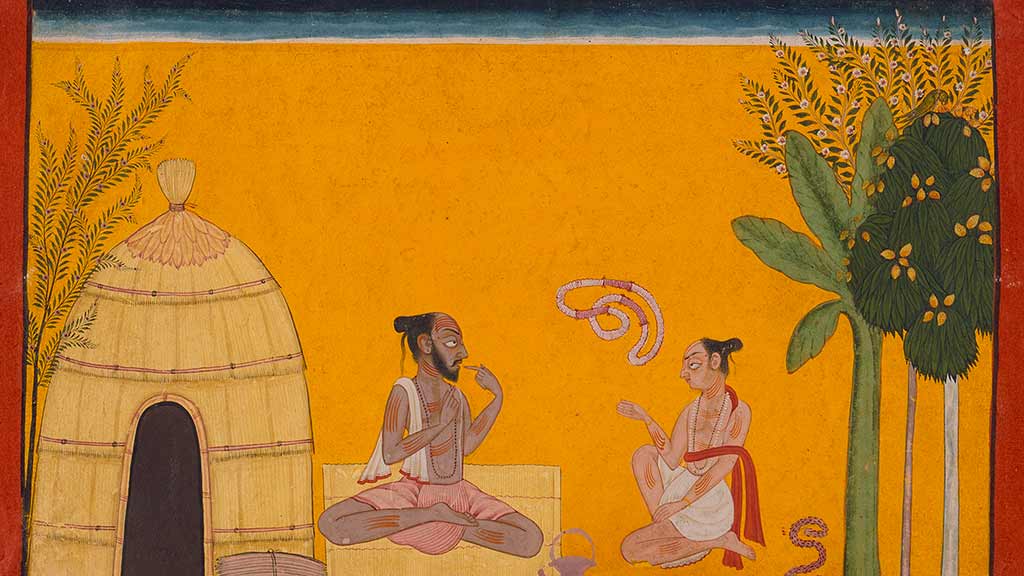

- The Story of Vālmīkī Rāmāyana

- Global Receptions of the Rāmāyana

- The Vālmīkī Rāmāyana: A Timeless Hindu Tale at the Spurlock Museum of World Cultures

The impact of the Rāmāyana on global receptions of antiquity is significant. Like the Mahābhārata, the Rāmāyana offers a glimpse into the life of the ancient Indo-Aryans, whose culture and religion were transmitted to various parts of the world at different points in time. There are many artifacts housed in the Spurlock Museum that highlight the impact of the Rāmāyana on Southeast Asian cultures. Among the Spurlock collections, we find a carved wooden figurine from the Indonesian island of Bali representing the eagle Jatāyu. The artifact exemplifies the distinctive aesthetic practices of Balinese Hindu culture.

-

Figurine: "The Great Eagle Jatāyu Attempts to Rescue Sita from Rahwana," Scene from the Rāmāyana. Credit: Gift of Professor John Garvey Bali, Indonesia 20th century 2002.17.0011

Figurine: "The Great Eagle Jatāyu Attempts to Rescue Sita from Rahwana," Scene from the Rāmāyana. Credit: Gift of Professor John Garvey Bali, Indonesia 20th century 2002.17.0011

Jatāyu is a noble eagle who attempts to rescue Sītā from the clutches of Rāvana when she is abducted. He is the brother of Sampatti, another important character in the epic, and the nephew of Garuda, a giant bird who is the vehicle (vahana) of the god Vishnu. The figurine was exhibited in our discussion circle in the Collaboration and Community Gallery at the Spurlock.

The migration of the story from the Indian subcontinent to the Indonesian archipelago is fascinating, and many scholars have explored the subject. One recalls the Mataram kingdom ruled by the Mahayana Buddhist Shailendra dynasty and the Hindu Sanjaya dynasty. The Hindu court fled to Bali following the Muslim conquests of 1478. Archaeological remnants such as Angkor Wat(external link) and Prambanan(external link), where the scenes from the Rāmāyana are etched into stone, also reveal the lasting legacy of the Hindu-Buddhist legacy in other parts of Southeast Asia.

Murals from the Thai Ramkien were painted in the temple of the Emerald Buddha (Wat Phra Kaew(external link)) in the 18th century. There is also the Javanese Kakawin Ramayana(external link) (c. 870 CE, Medang Kingdom). A kakawin is a Javanese form of narrative poetry based on the Sanskrit poetic tradition. This poem is often linked to the Bhattikāvya, alternatively titled the Rāvanavahda (The Death of Ravana), a 7th-century CE primer on Sanskrit grammar in the tradition of Pānini focusing on the Rāmāyana.

-

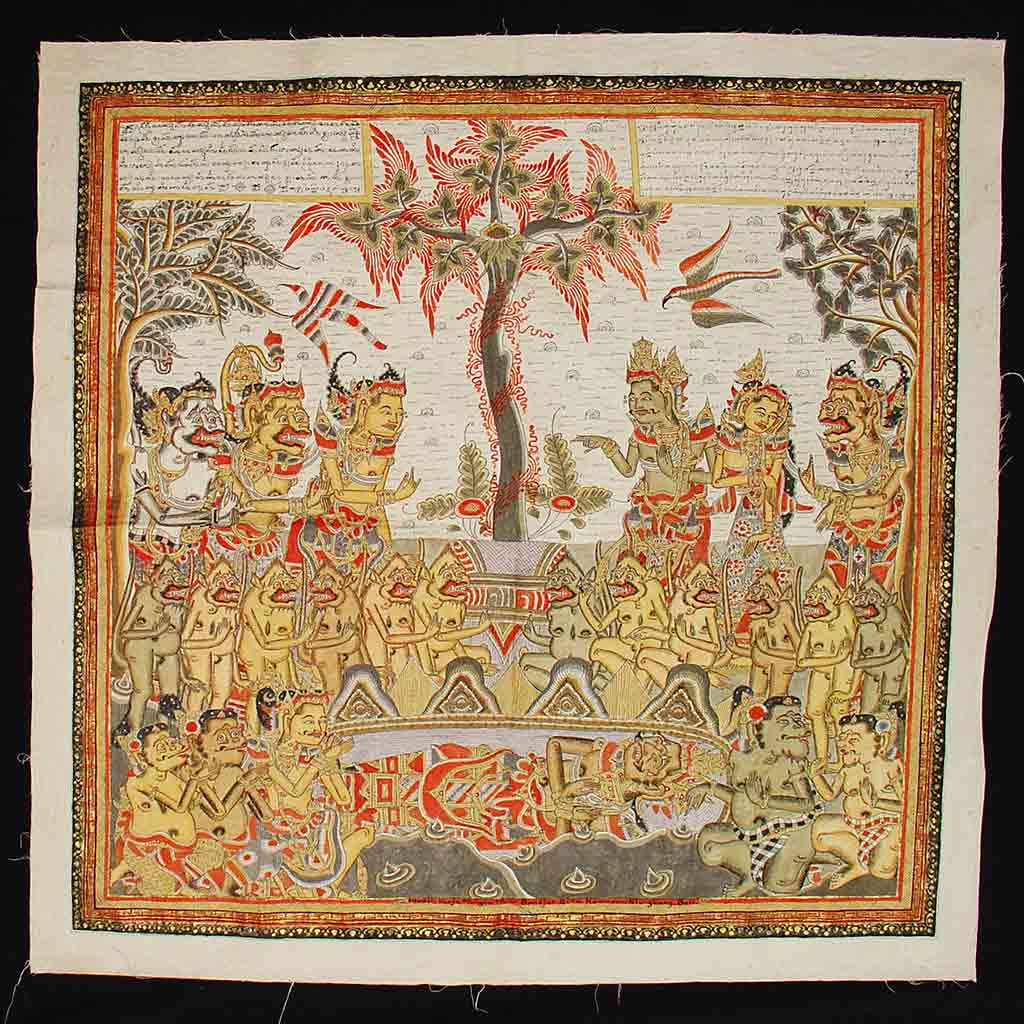

Painting: Rāmāyana scene, Death of Rahwana. Bali, Indonesia Late 20th century Credit: Estate of Dr. Robert E. Brown 2012.07.0088

Painting: Rāmāyana scene, Death of Rahwana. Bali, Indonesia Late 20th century Credit: Estate of Dr. Robert E. Brown 2012.07.0088 -

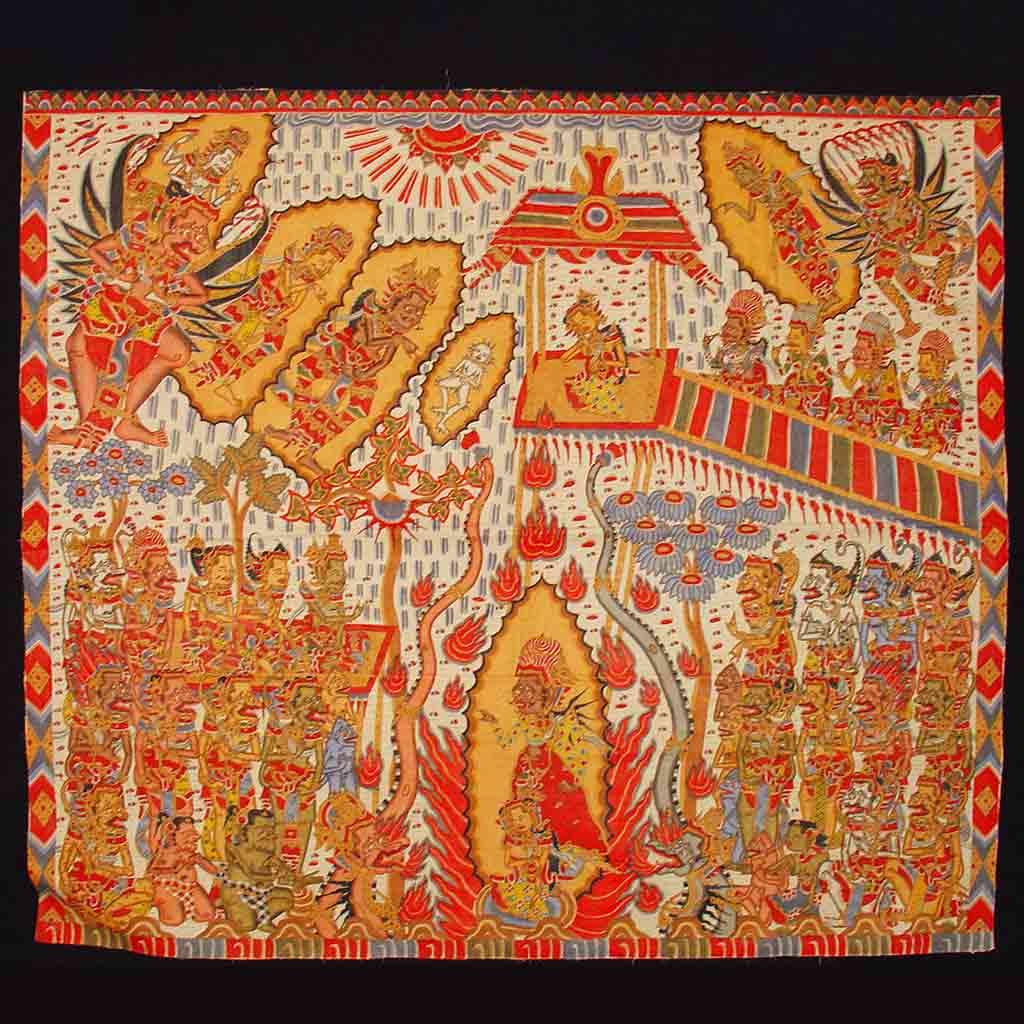

Cloth Painting: "Sita's Trial by Fire," scene from the Rāmāyana Bali, Indonesia 20th century Credit: Gift of Professor John Garvey 2002.17.0025

Cloth Painting: "Sita's Trial by Fire," scene from the Rāmāyana Bali, Indonesia 20th century Credit: Gift of Professor John Garvey 2002.17.0025

Balinese cloth paintings depicting key scenes in the epic, namely Sītā’s Trial by Fire and the Death of Rāvana, can also be viewed in the Spurlock’s collections. Balinese cloth painting(external link) is a cherished tradition using materials and methods indigenous to the island. One also finds among Spurlock’s collection wayang kulit shadow puppets and Javanese wayang golek wood puppets, some of which are related to the Rāmāyana.

-

Wayang Kulit (Shadow Puppet) Bali, Indonesia 1989 Credit: Gift of Krannert Center for the Performing Arts Costume Shop, UIUC 1989.10.0040

Wayang Kulit (Shadow Puppet) Bali, Indonesia 1989 Credit: Gift of Krannert Center for the Performing Arts Costume Shop, UIUC 1989.10.0040 -

Wayang Kulit (Shadow Puppet) Bali, Indonesia 1989 Credit: Gift of Krannert Center for the Performing Arts Costume Shop, UIUC 1989.10.0042

Wayang Kulit (Shadow Puppet) Bali, Indonesia 1989 Credit: Gift of Krannert Center for the Performing Arts Costume Shop, UIUC 1989.10.0042 -

Wayang Kulit (Shadow Puppet): Demon: Rahwana Bali, Indonesia 2005 2005.08.0002

Wayang Kulit (Shadow Puppet): Demon: Rahwana Bali, Indonesia 2005 2005.08.0002

As such, these folk artistic traditions are interconnected. As Leland W. Gralapp points out, “The space concept of Balinese painting closely resembles the patternization of the shadow-play, while the conventional attitudes and gestures of both human figures echo those of dance performers.” These aesthetic practices were used by Balinese artisans to re-imagine the Rāmāyana, Mahābhārata, and other stories in the 20th and 21st centuries. In modern-day Indonesia, the Rāmāyana ballet Prambanam retells the Rāmāyana for contemporary audiences using the wayang tradition; it is designated by UNESCO as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Cambodian theatrical masks for depicting the Rāmāyana are also found in the Spurlock collections.

We may link these Indonesian traditions of shadow puppetry to the Southern states of India where at least eighteen variants of shadow puppetry have been recorded(external link). Many scholars trace the influence of the Rāmāyana on Chinese literature via trade routes linking China to Southeast Asia. As Chih-tsing Hsia writes in History of Chinese Shadow Theatre, the Indian influence on the medieval Song dynasty came by way of Southeast Asia where Rāmāyana was enacted through folk traditions.

Hanuman, a key character in Rāmāyana, is a predecessor of the monkey Sun Wukong’s Journey to the West, a 16th-century Chinese novel. Many of the details in Investiture of the Gods (c. 1567–1619) can be traced to Theravada Buddhist sutras, a sect of Buddhism common to Southeast Asia. Indeed, a vibrant tradition of Rāmāyana storytelling emerged in Buddhist Jataka tales patterned on the Hindu story, most notably the Dasaratha Jataka, where King Dasaratha is the monarch of Benares, not Ayodhya, and Rāmā is depicted as a previous incarnation of the Buddha.

Localized interpretations of the Rāmāyana abound in Southeast Asia, where the Hindu story fused with indigenous elements. The Khmer interpretation of the Rāmāyana is called Reamker(external link) (The Glory of Rama). In Laos, the Rāmāyana is known as Phra Lak Phra Ram—Phra Lak refers to Lakshmanā and Phra Ram is Rāmā. In Thailand, the Rāmāyana was adapted as Ramakien. In Malaysia the story became known as Hikayat Seri Rama and in Burma Rama Yagan. Parul Dhar notes that “the Tamil oral tradition has influenced the Hikayat Seri Rama and other mainland Rāmāyana narratives in Thailand and Cambodia.” Important variations in the story exist in these adaptations that deviate from Indian variants.

-

Amulet: Rama the 5th Buddha Bangkok, Thailand 1994 Credit: Kieffer-Lopez Collection 2008.22.0245A

Amulet: Rama the 5th Buddha Bangkok, Thailand 1994 Credit: Kieffer-Lopez Collection 2008.22.0245A

-

Rubbing from Temple Relief: Rāmāyana(?) scene, Ogres in Procession. Thailand 20th century Credit: Estate of Robert E. Brown 2012.07.0006

Rubbing from Temple Relief: Rāmāyana(?) scene, Ogres in Procession. Thailand 20th century Credit: Estate of Robert E. Brown 2012.07.0006

Similarly, the Rāmāyana has tremendously impacted scholars, artists, and writers in the western hemisphere. The German scholar Augustus Schlegel produced an incomplete translation in 1829. The French Indologist Hippolyte Fauche translated the Rāmāyana in the 1850s. The young Indian poet Toru Dutt, who resided in England and France in the late 19th century, penned a poem called “Lakshman,” based on the Rāmāyana and included in her anthology Ancient Ballads and Legends of Hindustan (1882). Two late 19th-century poems by Leconte de Lisle, of the French Parnassian movement, “Çunacépa” and “La mort de Valmiki,” were inspired by the Rāmāyana. Fernand Cormon, whose students included Toulouse-Lautrec and Van Gogh, produced a painting in 1875. In his notebooks, Ralph Waldo Emerson refers to “Valmiki, author of the Rāmāyana" as well as “Vyasa, the compiler of the Mahabharata” in his notes on “Hindoo history.”

-

Fernand Cormon, "Mort de Ravana" Thailand 1875 Oil on canvas Musee des Augustines, Wikimedia Commons

Fernand Cormon, "Mort de Ravana" Thailand 1875 Oil on canvas Musee des Augustines, Wikimedia Commons

Modern dramatic interpretations of the Rāmāyana are plentiful. Rāmlila, the traditional performance of the Rāmāyana based on the Rāmcharitmānas of Tulsidās, which includes song, narration, dialogue, and recital, is performed throughout northern India during the Dusshera festival. It has been designated as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO(external link). In 2023, the Texas Asia Society staged a production of the Rāmāyana called Transcending Borders: The Rāmāyana Project(external link) featuring Indian, Indonesian, and Sri Lankan dance troupes. The 45th annual musical "Rāmāyana!” will be staged at the Mount Madonna School in California in 2024; the program was inspired by Baba Hari Dass (Babaji), a silent monk, teacher, and practitioner of yoga from India.

In this way, we see that the Rāmāyana remains a living, breathing heritage, providing refuge and prompting reflection age after age for diverse audiences throughout the world. Our Rāmāyana storytelling circle at the Spurlock Museum contributed to this rich legacy of Rāmāyana’s enduring impact on global humanity.

However, it is worth emphasizing that in the Hindu tradition, the Rāmāyana is not simply literature or history but scripture. History refers to events that took place in the past. Many have understood Rāmā’s story in terms of history—that is, in terms of time. However, history is bound by time and space. Likewise, others have seen Rāmāyana as a literary text, as an epic poem in the Sanskrit literary tradition. Many artists have tried to paint him as well. However, this suggests that Rāmā, who is considered divine, can be bound by the artist’s imagination. As Swami Tyagananda points out in his essay, Understanding Rāmā(external link), “Scripture is the truth authenticated by direct experience.” As such, what differentiates the Rāmā of scripture from the historical and literary variants is that he “can be experienced in the heart directly and intensely” by spiritual seekers, allowing them to develop a relationship with the transcendental.

-

- Share: 𝕏

- Subscribe to Newletter

- Giving